OAuth has become the backbone of modern authentication and authorization systems. It powers API access, mobile applications, SaaS integrations, service-to-service communication, and identity federation across organizations.

It is often treated as a solved problem. It is not.

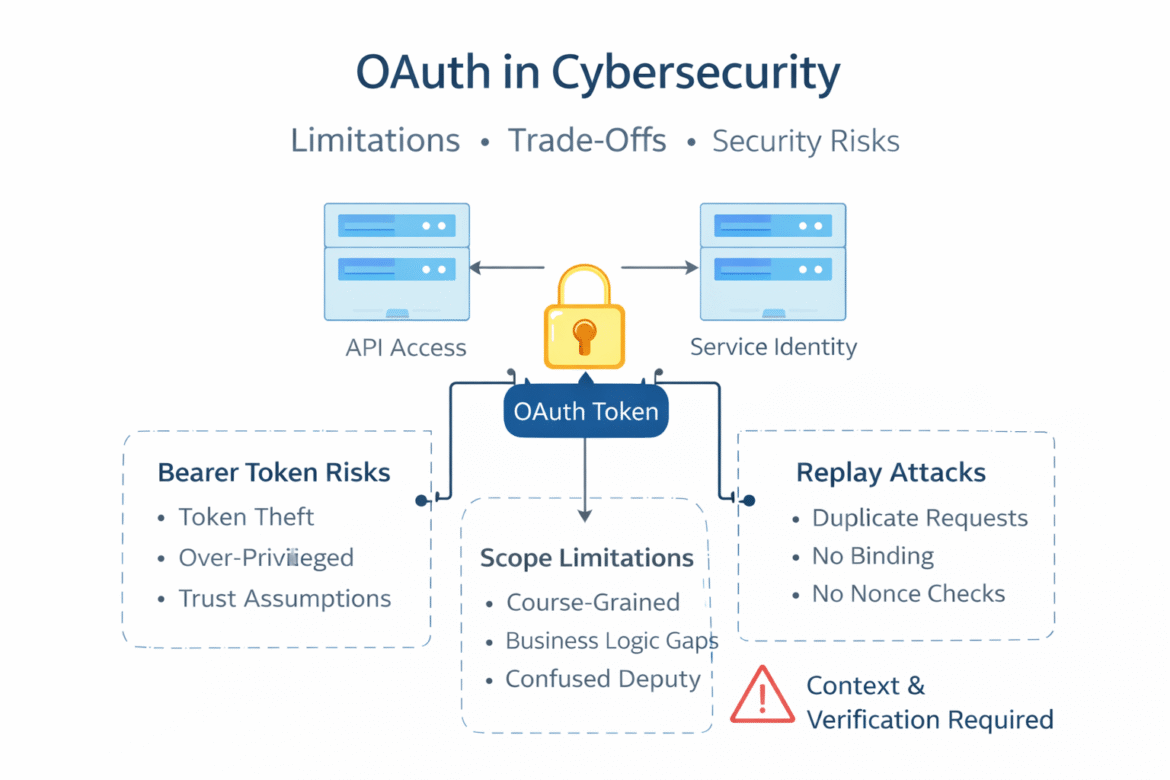

OAuth is a powerful delegation framework, but it is frequently misunderstood, misapplied, or over-trusted. Its flexibility is both its strength and its weakness. Understanding OAuth’s limitations and trade-offs is essential for designing secure distributed systems.

This article explores where OAuth succeeds, where it struggles, and the architectural trade-offs it introduces.

What OAuth Actually Solves

OAuth is fundamentally a delegation protocol.

It allows:

- A client to obtain limited access to a resource

- Without sharing user credentials

- Using a token issued by an authorization server

OAuth does not:

- Authenticate users by itself (OpenID Connect adds identity)

- Guarantee fine-grained authorization

- Protect against misuse of over-privileged tokens

- Enforce business logic constraints

It provides a framework. Security still depends on implementation discipline.

The First Limitation: Tokens Are Bearer Instruments

Most OAuth deployments use bearer tokens. Whoever holds the token can use it.

There is no built-in proof that:

- The caller is the legitimate holder

- The request context matches the original intent

- The token is being used on the expected device or service

If a bearer token is:

- Logged

- Cached insecurely

- Exposed via browser storage

- Intercepted through misconfigured TLS

It can be replayed.

Trade-off

Bearer tokens are simple and interoperable. Proof-of-possession mechanisms (e.g., mTLS, DPoP) increase security but reduce compatibility and operational simplicity. Simplicity wins often. Security loses quietly.

The Second Limitation: Scope Is Not Granular Enough

OAuth relies heavily on scopes to define access.

Examples:

readwriteadminpayments:read

In practice:

- Scopes become coarse-grained

- New scopes accumulate over time

- Clients are granted broader scopes “temporarily”

Scopes are rarely tied to:

- Context

- Risk level

- Frequency of operation

- Real-time user intent

Trade-off

Fine-grained authorization requires:

- Policy engines

- Attribute-based access control

- Runtime context evaluation

That adds architectural complexity. Many systems settle for coarse scopes.

The Third Limitation: OAuth Solves Authentication, Not Authorization Logic

OAuth validates:

- Who the client is

- What scopes it has

It does not validate:

- Whether this specific action is appropriate

- Whether the request aligns with business rules

- Whether the downstream impact is acceptable

This leads to common failures:

- Confused deputy scenarios

- Privilege mismatch between service and user

- Indirect abuse via trusted services

Trade-off

Centralizing authorization in OAuth simplifies trust. Distributing fine-grained authorization across services increases safety but requires consistent enforcement.

The Fourth Limitation: Machine Identity Sprawl

In modern architectures, especially microservices and A2A integrations, OAuth is used with client credentials flows. Each service becomes:

- An identity

- A token holder

- A security principal

Over time:

- Service accounts proliferate

- Secrets are duplicated

- Privileges grow but rarely shrink

Unlike human users, service identities:

- Do not rotate naturally

- Do not notice anomalies

- Do not question unusual access

Trade-off

Service-to-service OAuth enables automation and scalability. It also expands the blast radius of compromised credentials.

The Fifth Limitation: Token Validation Assumptions

Resource servers frequently:

- Trust JWTs without introspection

- Skip audience validation

- Fail to enforce token expiration strictly

- Ignore issuer constraints

JWT validation often becomes a copy-paste middleware operation. The presence of a valid signature does not guarantee:

- Correct audience

- Correct scope interpretation

- Correct tenant isolation

Trade-off

Self-contained JWTs reduce dependency on authorization servers and improve performance. Introspection increases control but adds latency and infrastructure reliance.

The Sixth Limitation: OAuth Does Not Address Replay Well

Even short-lived tokens can be replayed within their validity window. OAuth by default does not enforce:

- Nonce requirements

- Per-request uniqueness

- Device binding

- IP constraints

Replay attacks become especially relevant in:

- A2A systems

- Webhook-based integrations

- High-value APIs

Trade-off

Replay protection requires:

- Token binding

- mTLS

- DPoP

- Additional state tracking

These mechanisms increase operational overhead and reduce ecosystem compatibility.

The Seventh Limitation: Human Factors and Misconfiguration

OAuth complexity creates misconfiguration risk. Common issues:

- Incorrect redirect URI validation

- Improper PKCE implementation

- Overly permissive CORS

- Token storage in insecure browser contexts

The protocol itself may be sound, but implementation errors dominate real-world breaches.

Trade-off

OAuth’s flexibility allows broad adoption. Flexibility also creates configuration drift and inconsistent enforcement.

Where OAuth Excels

Despite its limitations, OAuth remains powerful when:

- Used with strict scope discipline

- Combined with policy engines for action-level authorization

- Protected with TLS everywhere

- Augmented with step-up authentication for high-risk actions

- Audited with strong logging and traceability

OAuth provides a scalable trust delegation mechanism. It does not replace architectural security thinking.

Rethinking OAuth in Modern Systems

OAuth should be treated as:

A foundation for trust delegation, not a complete security model.

Modern systems increasingly require:

- Context-aware authorization

- Risk-based decision engines

- Short-lived, scoped tokens

- Token binding or proof-of-possession mechanisms

- Explicit trust boundaries between services

When OAuth is used as a checkbox instead of an architectural component, weaknesses surface.

Closing Thoughts

OAuth is neither insecure nor sufficient. It is a protocol designed for delegation in distributed systems. Its real-world security depends on how it is implemented, scoped, validated, and constrained.

Understanding its limitations is not an argument against using OAuth. It is an argument against assuming that OAuth alone guarantees secure systems.

Security does not emerge from tokens. It emerges from architecture, boundaries, and disciplined enforcement.

Leave a Reply